This exhibit, curated by Valerie Park MA '01 while she was Archivist in 2004, looks at a selection of student protests and instances of activism. The exhibit, and an accompanying presentation by Park, were part of the April 8, 2004 Teach-In on Racism, Bias, and Exclusion. Click here for the full text PDF of Valerie Park's presentation.

While attending Sarah Lawrence as a dance student, Carolyn Adams ’65 declared that students “have the facts of American history and [an] awareness of mistakes of the past to justify our present fight for equality” and implored her fellow students to engage in and remain vigilant in defense of civil rights. For six decades, Sarah Lawrence College students have actively sought to bring civil rights issues on campus and in our communities to light through benefit fundraising, sit-in picketing, march organizing, and teach-in educating. This exhibit, drawn from materials housed in the Sarah Lawrence College Archives, celebrates their struggles. In recognition of current students’ continuing struggle to draw attention to racist behaviors and attitudes in our community and work towards their elimination, this exhibit highlights the long tradition of Sarah Lawrence student struggles for social justice within our campus community and in larger social and political arenas, with hope that we may learn from our history.

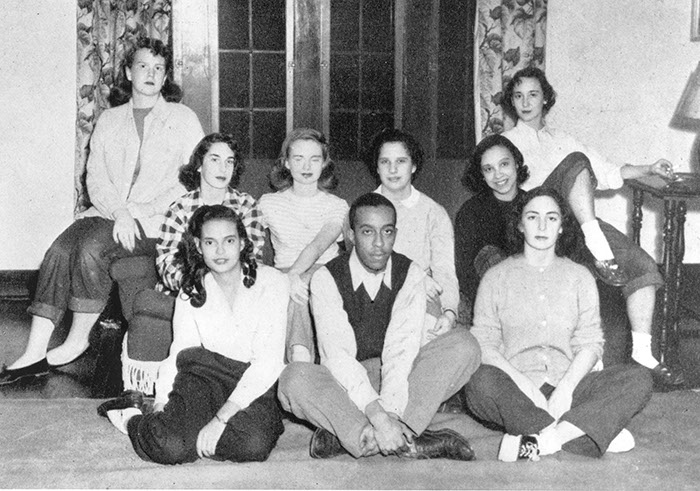

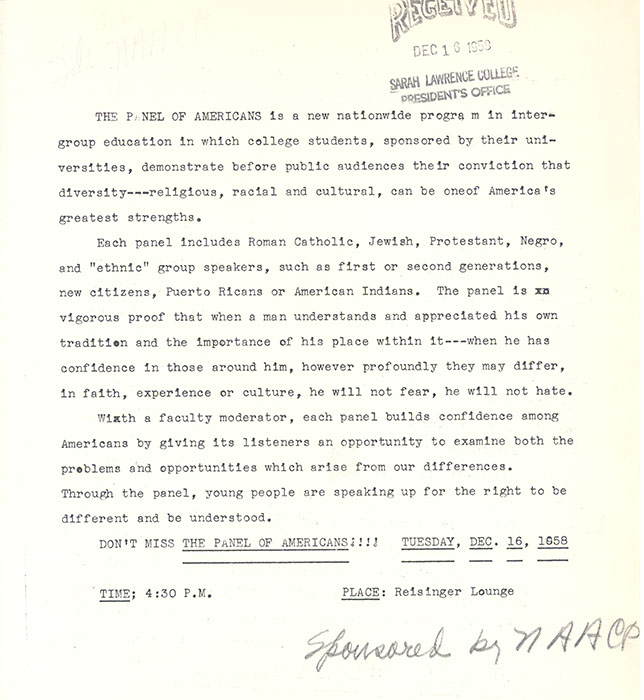

NAACP Chapter

Throughout the 1950s, the Sarah Lawrence chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (N.A.A.C.P.) took an active role in promoting civil rights. In 1953, the chapter organized an art exhibit to celebrate Negro History Week and planned dinners, concerts, and dances in the mid-50s to benefit the NAACP Scholarship Fund. 1958 marked increased activism amongst members of the chapter—in October, Sarah Lawrence students descended upon Washington, DC to participate in the Youth March for Integrated Schools, and in December, the chapter sponsored a “Panel of Americans” discussion, a teach-in designed to promote diversity and “inter-group” relations.

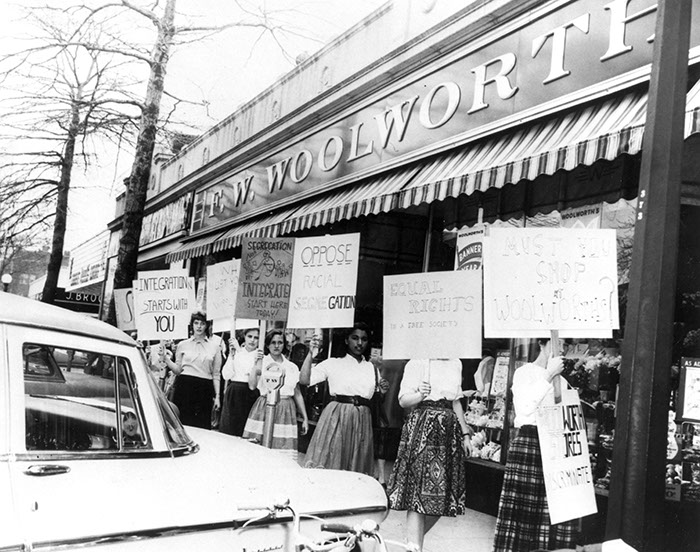

Bronxville Woolworths Picket, April 14, 1960

The movement toward civil rights by both Northern and Southern college students was not lost on Sarah Lawrence students. While Southern youths staged sit-ins protesting segregated lunch-counters in department store chains, the Sarah Lawrence chapter of the National Students Association (N.S.A.) coordinated a picket and boycott of the Bronxville Woolworths, a corporation notorious for its “whites-only” lunch-counters. Two weeks later, the N.S.A. sponsored a talk by Conrad Lynn, a lawyer for both the N.A.A.C.P. and the Civil Rights Union, and Marzette Watts, a student expelled from Alabama State University for his leadership in student activism in Montgomery, Alabama.

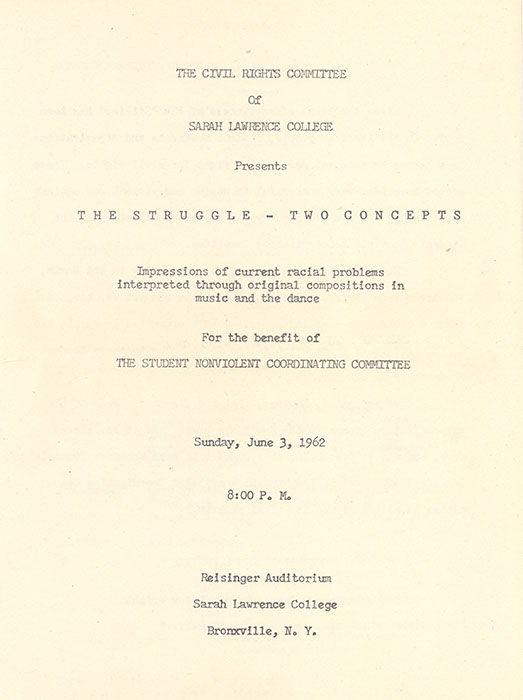

Civil Rights Committee Benefit Performance, June 3, 1962

Reisinger Auditorium served as the stage for the Sarah Lawrence College Civil Rights Committee’s presentation of the dance performance, THE STRUGGLE: TWO CONCEPTS, for the benefit of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (S.N.C.C.). The performance was described as an “impression of current racial problems interpreted through original compositions in music and dance” by composer John Churchville, a Columbia University student, and choreographer Carolyn Adams, a Sarah Lawrence student, class of 1965.

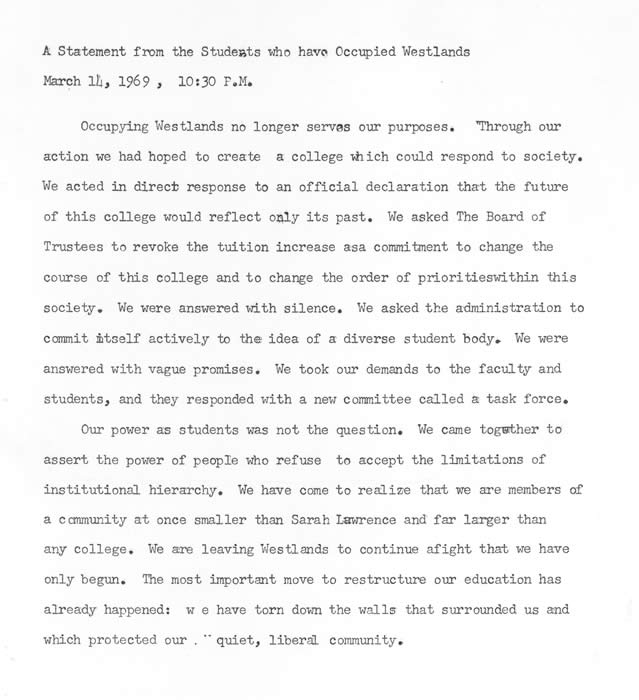

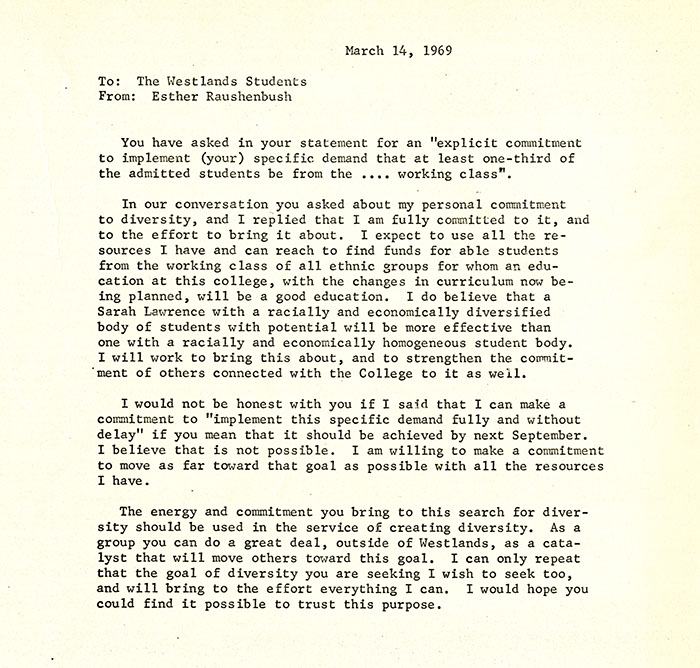

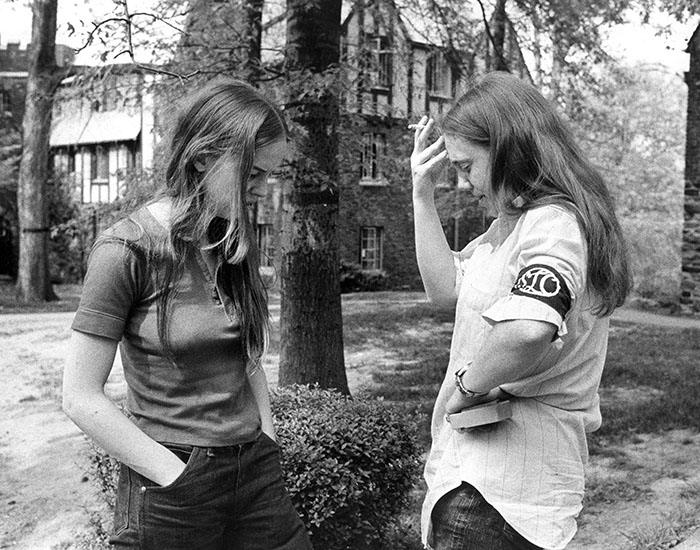

Westlands Sit-In March 5-14, 1969

The first sit-in occupation of Westlands in the history of Sarah Lawrence College began over the issue of a $350 tuition raise passed by the Board of Trustees for the 1969-1970 academic year. On March 5, students occupied Westlands to demand that the Board rescind the tuition increase which they feared would “increase the elitism” of the institution. The occupants demanded diversification through a “sexually, economically, and socially representative student body” and advocated restructuring the College to make it more affordable. Over the course of the sit-in, the occupants devised non-negotiable restructuring demands aimed at increasing student, faculty, and curricular diversity, which included the creation of a new admissions policy, the abolition of the existing admissions committee, the creation of joint student/faculty curricular and appointments committees, and a co-education policy. Essentially, the occupants felt that if the student body was more racially diverse, the College would benefit from grants from large foundations, thus alleviating the need for a tuition raise. However, by the tenth day of the sit-in, the administration still had not agreed to the non-negotiable demands and President Esther Raushenbush asked the occupants to vacate Westlands. After hearing unofficial and unconfirmed threats of suspension if the sit-in continued, the occupants issued a final demand, asking for an unqualified commitment to diversity. This demand was met by a statement from the administration supporting the idea of diversity, but indicated that total implementation would not be immediately possible.

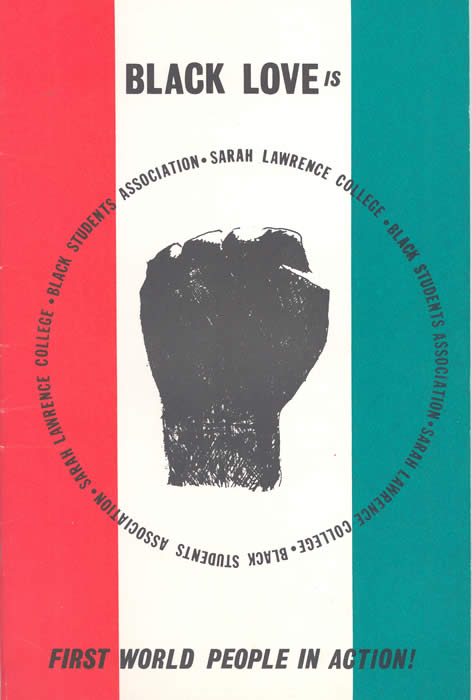

Black Students Association, 1969-1973

Although not at odds with the demands of the Westlands Sit-In occupants, the Black Students Association (B.S.A.) had already been discussing a funding and restructuring plan for diversification prior to the 1969 sit-in. On March 7, 1969, the B.S.A. presented a plan for the development of a Black Studies Social Change Program, outlining the necessity of increasing diversity in the student and faculty bodies and in the curricular offerings by admitting low-income and minority students, as well as hiring Black faculty to direct Black Studies courses and a Black coordinator to direct the above-mentioned program. On March 9, 1969 the College administration agreed to create a committee, called the Task Force for Black Studies and Social Change, to work with the members of the B.S.A. to achieve the goals of the organization. As a result, this committee secured the implementation of Black Studies courses, the hiring of four new Black faculty and the reappointment of two Black faculty, the addition of Black Studies periodicals and books to the library, and the creation of a lecture series featuring Black speakers and dealing with issues of “the Black experience.”

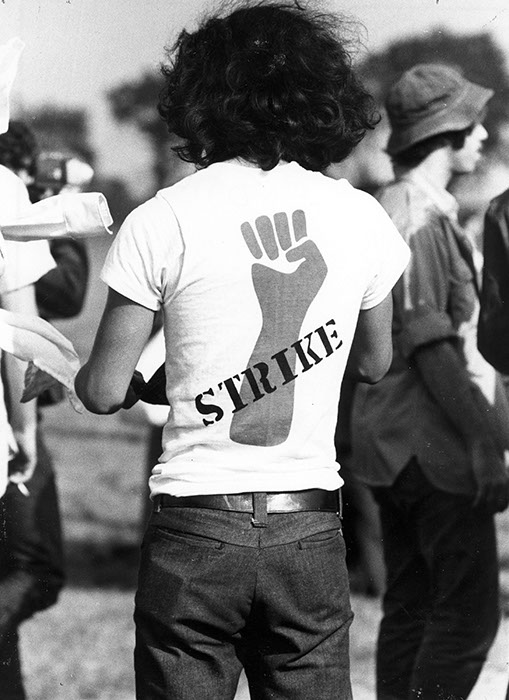

National Student Strike, May 4 - June 2, 1970

At the height of the Vietnam War, colleges across the country “closed down to open up” in a national strike, where faculty and students stopped "business as usual" in an effort to move into their local communities and to bring community members onto the campus to discuss and protest US military involvement in Southeast Asia, as well as homeland repression of political dissent. At Sarah Lawrence the college was, in no uncertain terms, on strike—98% of the faculty and 91% of the students voted in support of the National Student Strike. At Sarah Lawrence, throughout this month-long strike, numerous lectures were substituted for spring courses and made open to the public. In addition, students organized a variety of workshops on topics such as draft resistance, letter-writing campaigns, racism, and coordinated direct action initiatives in the form of candlelight vigils, guerilla theatre, and community canvassing and leafleting.

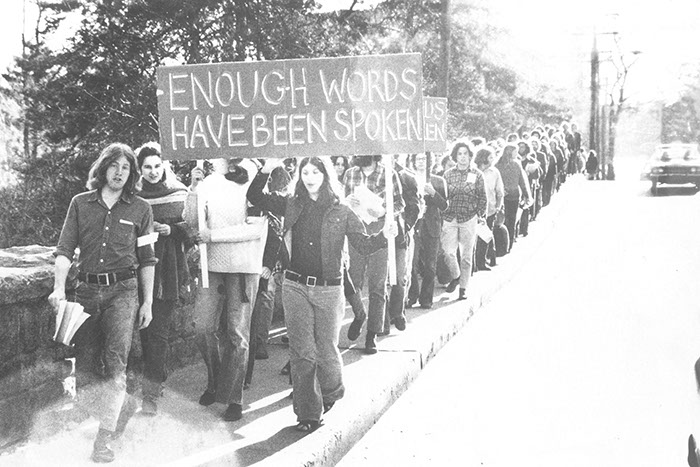

Silent Vigil for Peace, April 21, 1972

After further escalation of United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War, about 200 Sarah Lawrence students, faculty, staff, and local community residents marched into the Bronxville traffic circle to hold a silent peace vigil. For an hour and a half the group stood and gave out pamphlets to passers-by, one of which said, “March in New York tomorrow…not just another demonstration…this is an election year and Democrats and Republicans alike have to be reminded that Vietnam is a very real political issue.” After the vigil, the group marched back to campus and the vigil ended as silently as it had begun.

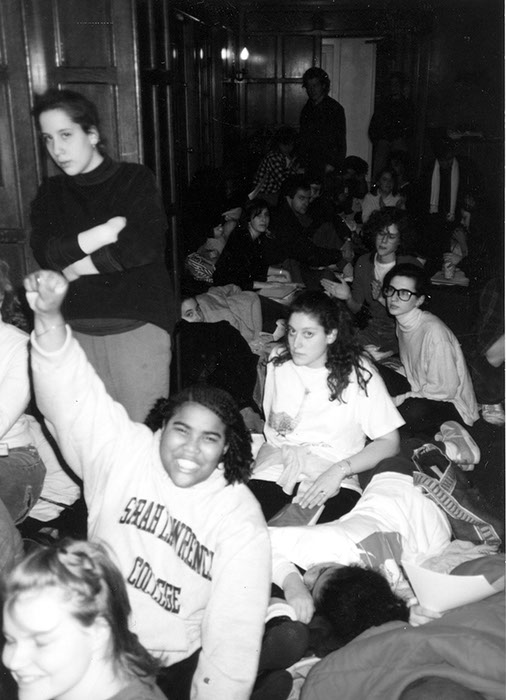

Westlands Sit-In, March 13-17, 1989

On February 28, 1989, a mural was painted in the Garrison dormitory depicting what many students felt were racist caricatures. A confrontation ensued between the painter and those offended by the mural. On March 1, the administration issued a statement declaring that the College “welcomes and nurtures people of all races” and “rejects all forms of racism,” and would not stand for further racist incidents. However, a coalition of students calling themselves Concerned Students of Color (C.S.O.C.) felt the administration’s statement was merely rhetorical. On March 8, the C.S.O.C. presented a list of demands to the administration, declaring that without structural change at Sarah Lawrence, the College could not justly claim to welcome and nurture all people of all races.

In short, the C.S.O.C. demanded tenure-track appointments of faculty of color, a center for people of color, and an administrator of multi-cultural affairs. Although the administration issued a reply, it was found unsatisfactory to the C.S.O.C. and by March 13, nearly 100 C.S.O.C. members and sympathizers began occupying Westlands. On March 15, an all-college meeting was called regarding the C.S.O.C. demands, but was largely boycotted by C.S.O.C. members who refused to leave Westlands. The next day a faculty-administration negotiating team was created and by March 17, following negotiations, the College committed itself to increase diversity and multiculturalism, and the Westlands occupants declared victory and ended the sit-in.

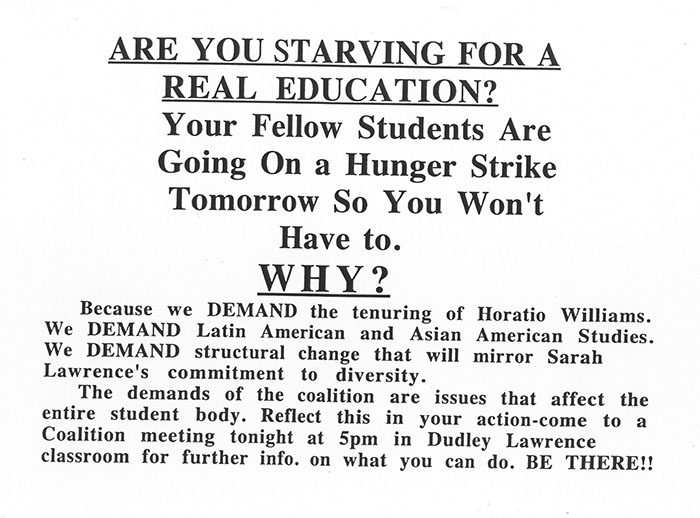

Hunger Strike, May 4-6, 1994

In the spring of 1994, sixteen Sarah Lawrence students began a hunger strike protest sparked by the College’s decision to deny tenure to political science professor Horatio Williams, a Liberian native, who was hired as a result of the College’s commitment to increase diversity following the 1989 Westlands Sit-In. The protesters, calling themselves “The Coalition,” vowed to subsist solely on water, fruit juice, and multivitamins until the College reversed William’s tenure denial. For two days, in meetings with the General Committee, the protesters demanded future student participation in the faculty hiring and tenure review processes. Moreover, the hunger strikers outlined goals aimed at the diversification the faculty body and the curriculum through the development of Latino-American, Asian-American, African-American, and Gay/Lesbian studies programs, the creation of study-abroad exchange programs in Latin America, Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean, as well as the an expansion of the Spanish Department to teach advanced Spanish courses. Finally, the protesters requested a space for students of color and permanent funding for conferences, lectures, and workshops sponsored by the Office of Multicultural Affairs. On May 6, although Williams was never granted tenure, the hunger strike was called off after the General Committee agreed to recommend review of the student’s concerns through the appropriate standing committees and offices of the College.

The OAR Report, 1996-1997

After attending a September 1996 orientation week workshop on writing and race taught by writing professor Suzanne Gardinier, a multiracial group of participants approached Gardinier expressing a desire to work toward eradicating racism at Sarah Lawrence, beyond consciousness-raising workshops. Throughout the academic year, Gardinier and this group of twenty-three students, called Organized Against Racism (O.A.R.), assembled this report. Their aim was to discover how racism works at Sarah Lawrence and how it might be changed. The lengthy O.A.R. Report includes: statistics tracking diversity in curricular offerings and amongst students, faculty, administrators and staff; an analysis of a campus-wide survey of experiences of racism; personal statements and interviews of students, alumnae/i, faculty, and administrators experiencing race and racism on campus; and finally, goals aimed towards making genuine racial diversity a reality at Sarah Lawrence College.