Beginning in 1941, with economics Professor Emma Llewellyn, students participated in field trips to the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). The trips, taken in conjunction with economics and other social science courses, offered the students a glimpse into the rural South and race relations that they could not find in books and educational films. Receiving national press coverage, the trips began as “extended group field trip[s] which the college catalogue had promised [but] became…major excursion[s] in race relations.” (Saturday Review, March 1, 1952)

Field Work, of which these trips are a part, has always, and still continues, to play an important role in a Sarah Lawrence education. Since the founding of the College in 1926, social responsibility and field work have been crucial elements in the curriculum. Constance Warren (President of the College, 1929-1945) in her 1939 book, A New Design for Women’s Education, reiterates the importance of field work:

“It is the business of the college to see that…students obtain an understanding of other viewpoints, other customs, other economic backgrounds, other values than the ones with which they are familiar.” (page 183)

This is exactly what the faculty hoped for the students to learn when they traveled down to Tennessee.

Emma Llewellyn, with her husband, Carl, organized the first of four trips taken to the TVA. She explained to the Curriculum Committee in January, 1941 that the reason for the trip was to teach students more about agriculture and the economy. She stated, “Students…have very little knowledge of the place of agriculture in our economy.” In order for students to fully grasp this knowledge, students participated in four trips to the TVA over a span of 15 years.

Only five students participated in the 1941 trip by car, while thirty students loaded onto the bus for the last trip in 1955. Each trip was slightly different resulting in different experiences for the students and faculty. However, the common threads through all the trips were the lessons learned in race relations, tolerance, segregation, agriculture and the rural South. The professors who participated in the excursions were Edward Solomon, Emma Llewellyn, Charles Trinkaus, Irving Goldman, Bert James Loewenberg, Edith Yalden-Thomson, and Albert Lauterbach.

This exhibit examines the impact these trips had on the students and faculty that participated and the importance of the field trips in relation to the College curriculum.

Why Tennessee? A Brief History of the Tennessee Valley Authority

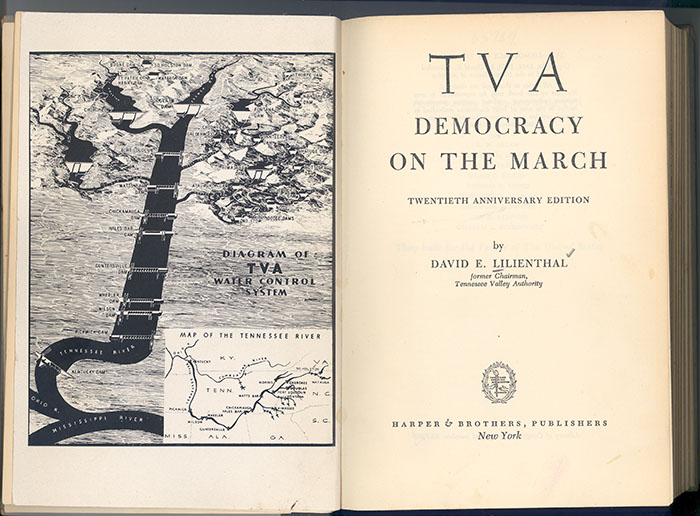

On May 18, 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the “Tennessee Valley Authority Act.” The Act stated that TVA was to set forth planning and development of the Tennessee River basin. This region includes seven states—Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi—with the majority of the region in the Tennessee valley. TVA was profound because it was the first federal government corporate agency to cross state boundaries and take on development of an entire region. Along with its integrated approach to development, the agency was based in the Tennessee Valley region rather than Washington, DC. Citing these two factors, government and TVA officials considered the program an “experiment” in democratic development.

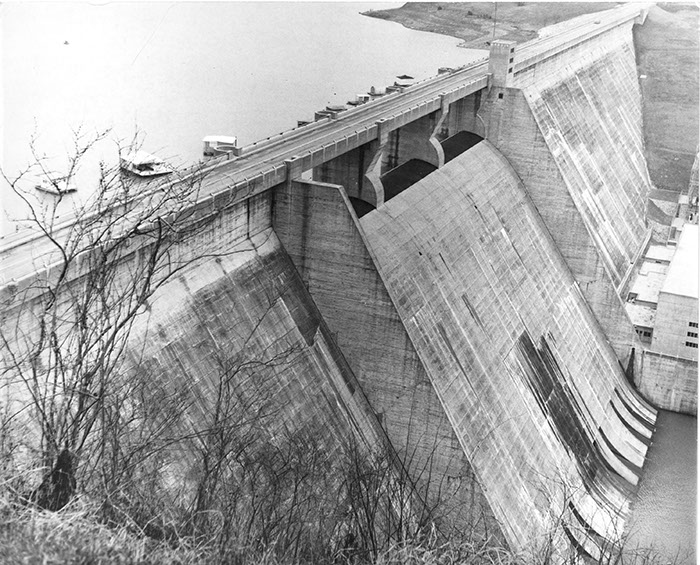

TVA was multifaceted in its goals and created programs to address flood control, reforestation, national defense, and agricultural and industrial development. In the midst of the Great Depression, TVA was seen as an agency that could provide economic uplift to the Tennessee valley. In the 1930s and 1940s the agency and its university affiliates worked with farmers, whose crops had been depleted by erosion and land overuse, to develop new fertilizers and farming techniques. TVA is perhaps most widely known as the agency that built a system of dams and lakes that forced hundreds of people to relocate. TVA then set up hydroelectric systems that contributed to the spread of electricity throughout the rural South. The power plants constructed by TVA supplied low-cost electricity to millions of residents, allowed for the relocation of industries to the South, and provided a base for the construction of national defense programs.

Itineraries

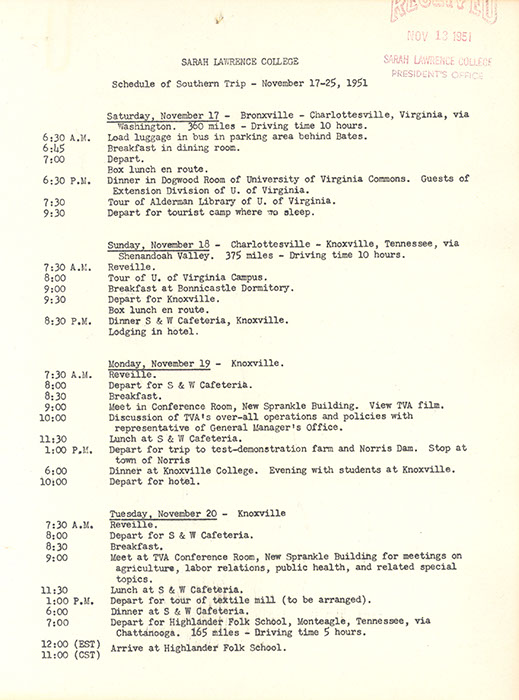

What did the professors hope students would get out of going to TVA? Professor Emma Llewellyn, the organizer of the first trip to the TVA in 1941, felt that the students taking economics needed a hands-on experience to learn the true place of agriculture in the United States economy. Edward Solomon, director of field work, stated the reason for the 1951 field trip to the TVA as follows: “The purpose of this trip is to give students first-hand knowledge about the problems and possibilities of planning for a whole region by a supra-governmental agency concerning flood control, navigation, the production and uses of electrical power, and other programs related to the general social needs of the people in the region.” (Field Work Report, October 1951) The breadth of their trips is apparent in the lengthy itineraries established for the trips. An example is seen here in page 1 of the itinerary of the 1951 trip.

Students Protest

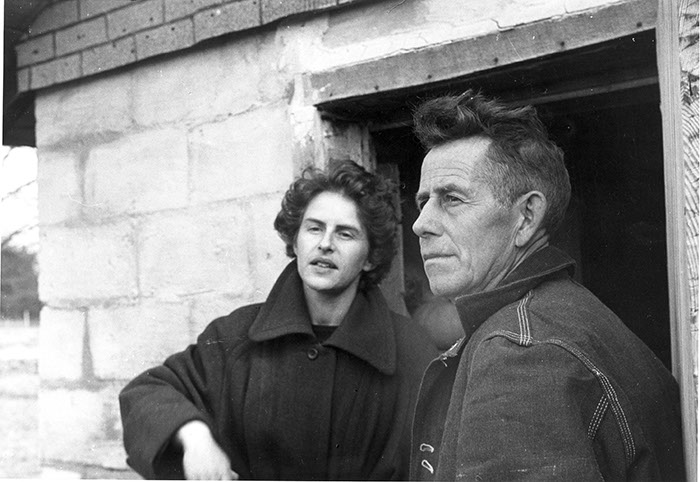

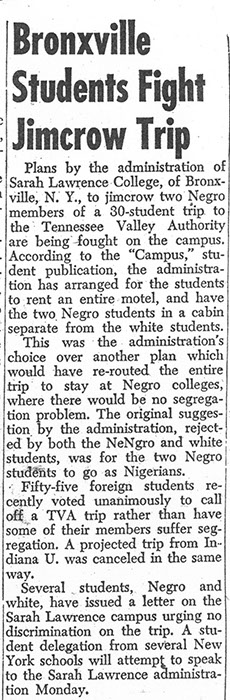

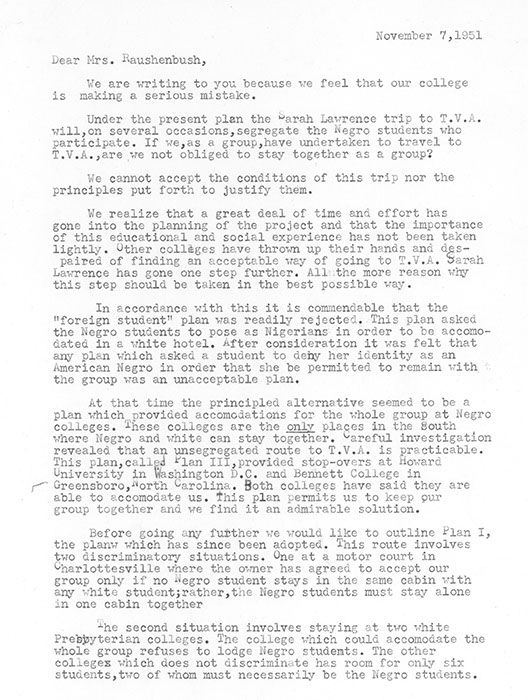

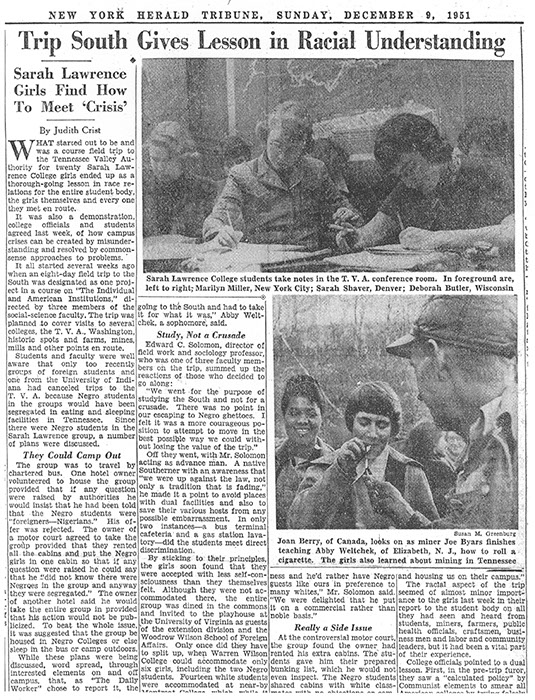

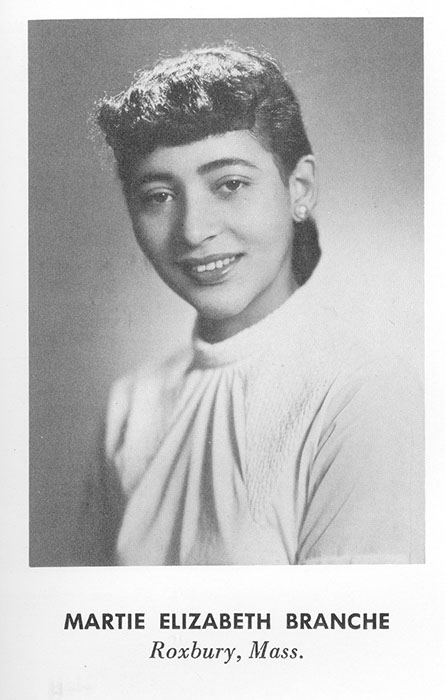

The second trip to the Tennessee valley was arranged to depart on November 17, 1951. The trip was directly associated with the course The Individual and American Institutions jointly taught by Bert Loewenberg, Emma Llewellyn, and Edward Solomon. Students outside these courses were invited to attend as well. A total of 23 students signed up. The details of the trip were arranged by Edward Solomon, field work director. Two of the students who signed up for the trip were first-year Joan Berry and junior Martie Branche, both Black. Originally, a number of the hotels and colleges the students planned on visiting only allowed segregated housing. However, as a result of the protest by students, Edward Solomon altered their plans and arranged integrated places to stay. This was not an easy task in the Jim Crow South.

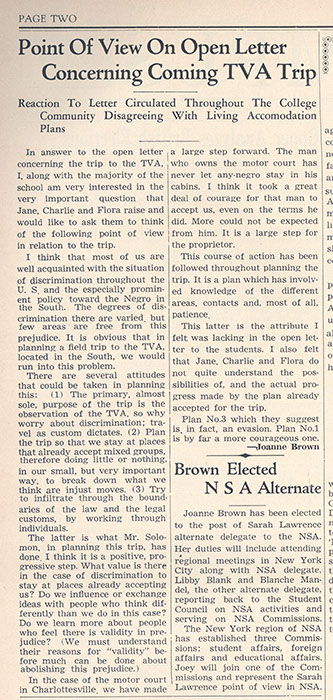

During a politically and racially charged time in the United States, the students at Sarah Lawrence were politically active. Originally, the College adopted three separate plans for dealing with segregated housing in the South. Plan I was that the students would stay in a motor court in which the owner was prepared to “evade both law and custom and serve both white and Negro students, his single stipulation being that, for his protection, the Negro students room together in the motor court they all occupy.” Plan II, the most controversial plan, requested that the Black students traveling on the trip portray themselves as Nigerian students visiting the United States in order to be able to stay together in segregated housing. In Plan III, students would stay in Black colleges so that both the white and Black students could room together.

Amidst protest and discussion by the faculty and students, Plan II was rejected. The options of Plan I and Plan III remained on the table in early November, 1951. When the College decided to proceed with Plan I in which the students would all stay in the same motor court, but the Black students must sleep separately, three students protested. Having already signed up for the trip, they distributed a letter of protest on November 7, 1951 requesting that the College adopt Plan III, staying in Black colleges, as the solution instead of Plan I. These students saw Plan III as “avoid[ing]…unnecessary segregation.” They went on to say, “We cannot consider plan III as merely another compromise; it is the only plan which permits us to stay together as a group. It is the only plan which asks no one to submit to personal humiliation.” Despite this protest, a debate in the student newspaper, The Campus, and an all-College meeting with President Harold Taylor on the subject, Plan I was used. It turned out in the end that the owner of the motor court allowed the students to room with whomever they chose and did not separate the white and Black students.

Segregation and Race Relations

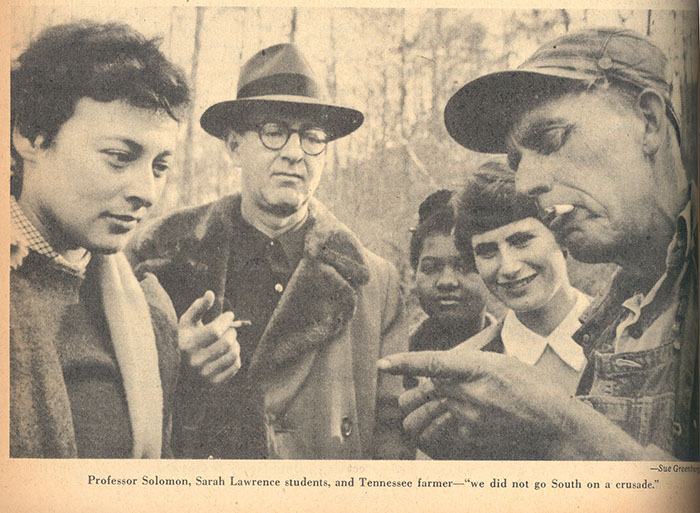

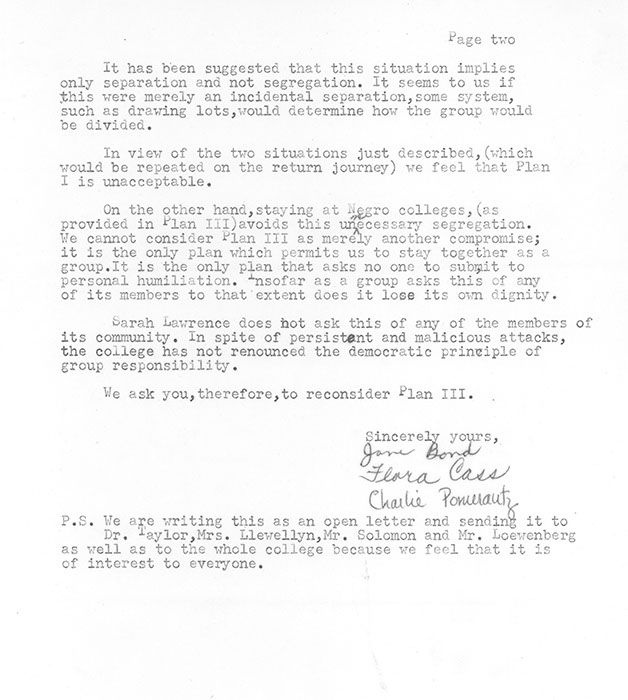

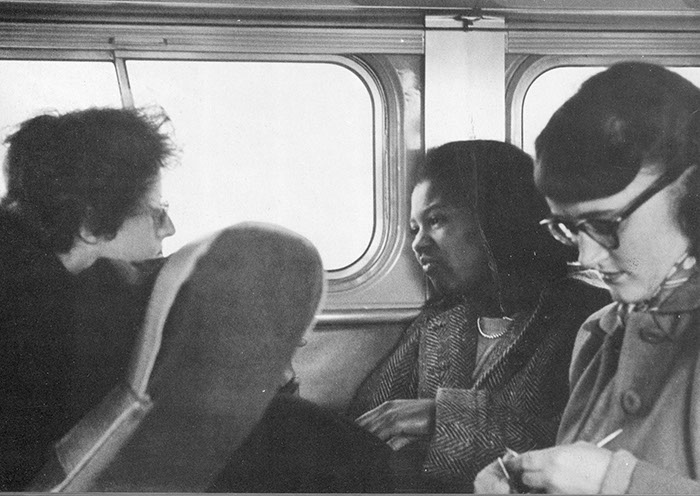

Before the 1951 TVA trip even began, it became apparent to students that they would learn more than mere economics. The Herald Tribune published an article on the trip in December, 1951 which stated, “What started out to be…a field trip to the Tennessee Valley Authority for twenty Sarah Lawrence College girls ended up as a thorough-going lesson in race relations for the entire student body.” The students experienced segregation and Jim Crow laws first-hand as they traveled through the South by bus. One student recalls the difficulty of using segregated bathrooms en route. According to the Saturday Review on March 1, 1952, “[Edward] Solomon eliminated points of friction by using box lunches in lieu of several mid-day stops.” The trips allowed for students to learn how racial segregation affected all aspects of life in the South. “Aside from its study of TVA and its lesson in race relations the Sarah Lawrence field trip also provided an inspiration for other mixed groups who seek to meet and study in the South.”

"The issue at the college was, do we go down and set an example by making a fuss over segregation or do we try to communicate, show them how a mixed group lives together and let them judge for themselves.”

- Sue Greenburg '53 (from an article in the Herald Tribune, December 9, 1951)

The students on the 1954 and 1955 trips learned about racial discrimination in the South. The 1955 trip coincided with the recent Supreme Court decision on segregation in the schools making the trip even more prescient allowing the students to see first-hand the impact of the Supreme Court decision. President Taylor in his May, 1955 report wrote, “On the whole, the students returned with rather optimistic feelings about the future of race relations in the South.”

“I imagine that one of the most important impressions that the TVA trip made on me was that we could take the trip under our own terms and not have to bow to any disagreeable customs. It is remarkable that an interracial group could go into the south without incurring any unpleasant circumstances.”

-Martie Branche '53 (from an article in The Campus, December 12, 1951)

Life in the Rural South

In addition to visiting the offices of the Tennessee Valley Authority and experiencing racial segregation first-hand, students on these trips learned about rural life in the South. This aspect of the trip became more of a goal as the years went by. So much so that Edward Solomon in a report to President Taylor in October 1955 wrote, “the discussion has suggested that less emphasis should be placed on power (Oak Ridge and the Kingston Steam Plant) and more on the culture of the rural area around Fontana Village and the institutional services available there.”

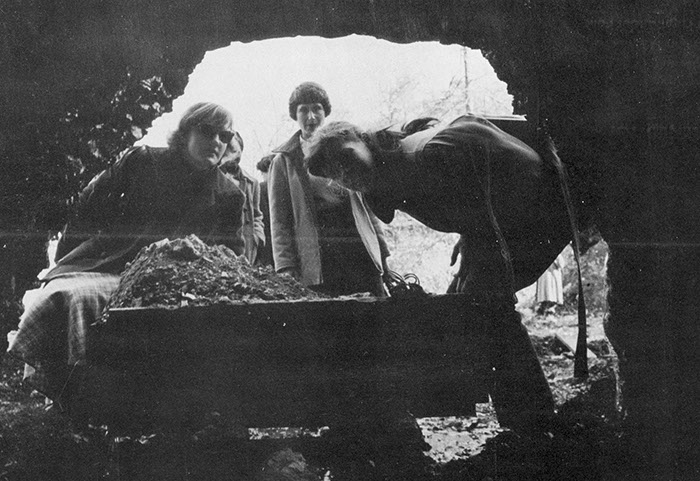

During the 1951 trip, students spent three days at the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee. The goal of their stay was to “put [them] in touch with local farmers, miners, trade union people and others, who could help [them] in achieving a better understanding of that area of the south.” (letter from Ed Solomon to Myles Horton of the Highlander School in September, 1951) At the Highlander School, students spent time “folk singing and square dancing” and generally “having fun with the local folk.”

The students had various impressions of rural life in the South. Deborah Butler stated in 1951, “Tennessee, lovely, but still so poor in many instances, with here and there a farm where the corn was still being planted on the hillsides and the stalks were broken and dead and the red soil washed away in gullies; and we wondered at how much worse it must have been before TVA came in.” (The Campus, December 12, 1951)

“Previous to the T.V.A. trip I had rather a distorted view of the South gleaned mostly from my knowledge of the Civil War and ‘Gone With the Wind.’ Our Southern trip was, therefore, an eye-opener to me.” “Fontana, the Cherokee reservation, Knoxville College, even our hotels, all combined to give me a picture of the South in its diversity.”

- Mary Champeny (from The Campus April 13, 1955)

“Sue McClain smiled, adding that traveling to the South certainly dispelled her prejudices of its being completely poverty stricken. This seemed to be a general feeling, though the tour didn’t go into the worst areas, it did touch the periphery that was representative of this changed, relaxed life among the people.”

- Excerpt from an article by Cynthia Robinson '58 in The Campus, April 13, 1955

“After frolicking in the pastures and gamboling with the cows, (are these pigs? Sheila Navarick inquired), we headed for Knoxville College (Negro, co-educational, Presbyterian) and had an informally delightful time talking and singing (folk songs, what else?) with students who gave us a spontaneous and heartwarming welcome ...On to Fontana Village, N.C. (a recreational project built by TVA and sold to private citizens) for a hillbilly square dance.”

- Joan Micklin '56 (from The Campus, April 14, 1954)

Learning About the T.V.A.

Even though the glimpse into rural life, segregation, race relations, and national monuments was significant, the final destination of each trip was the Tennessee Valley Authority. The goal of visiting the TVA was to “enable the group to examine at first hand flood and erosion control, navigation, production and consumption of electrical power, national defense programs, public health programs, employer-employee relations, municipal coops conservation and other social purposes. Two problems particularly occupying the interest of the students are that the politics behind the controversy over public and private power and that of the changing nature of a rural society to an industrial one.”

Before students left for the trips, they studied the development and history of the TVA through films and readings. While in Knoxville, at the headquarters of the TVA, students met with Raymond Paty, of the Board of Directors of the TVA, attended lectures, and visited factories, mines, farms, and dams.

"I had read pamphlets on the TVA and heard several men in various departments of the organizations give detailed accounts of the work carried on, but not until I saw the Norris and Watt's Bar Dams was the true picture of the vastness of the TVA undertaking ...impressed upon me."

"The three day sojourn in Knoxville was the busiest and most informative part of the trip." Talks given by men working for the TVA "ranged from general discussions about the origin, purpose and function of the TVA, race and labor relations, to the actual engineering problems of dam constructions.”

- Lois Checkers '56 (from an article in The Campus, April 13, 1955)

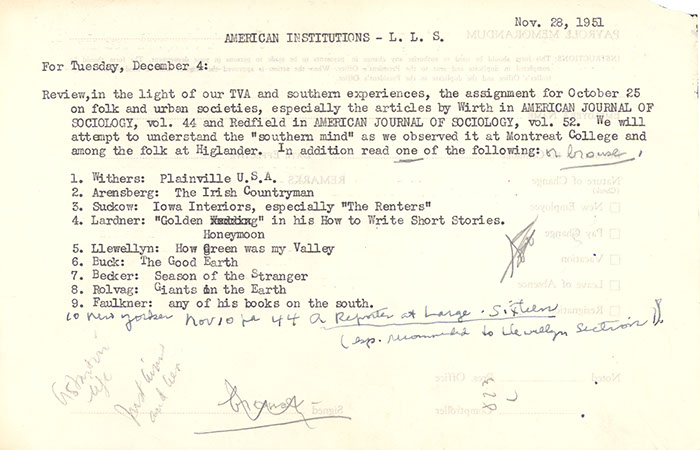

The course for the 1951 trip, The Individual and American Institutions, offered a background to students before they traveled down South. For instance, they watched educational films about the TVA and read numerous pamphlets and books on the subject. In addition to this joint course, students from other courses joined the trip. These courses were Irving Goldman’s Culture and Personality, Emma Llewellyn’s Exploratory Social Science, C. Martin Wilbur’s East Asia in Transition, and Edith Yalden-Thomson’s American Economic Policy and International Economics.

Faculty Involvement

The success of the TVA trips was a result of the faculty and the important role field work played in the Sarah Lawrence curriculum. Each faculty member who joined the students on these trips was intensely loved by the students. Following is a look at each faculty member involved with the trips along with their courses.

Emma Llewellyn (1897-1984) — Economics Faculty, 1938-1965

Emma Llewellyn’s course on Consumer Economics prompted her to request a trip to see the Tennessee Valley Authority working first-hand. She originally believed that 40 or 50 students would be interested, but only five eventually signed up. Apparently the social science faculty, according to a letter by Llewellyn, felt some “dubiousness…about the utility of any really organized trip under the circumstances…I feel distinctly badly about…the difficulty of getting our girls steamed up about anything so worth while. Still, for us it’s the first time we have been able to get even so many interested and it is said that things have to start somewhere.” Despite the difficulty of getting students interested in the TVA trip, Llewellyn and her husband, Carl, traveled with five students down South for an informative and innovative field trip. Fourteen years later, Llewellyn again went to visit the TVA with the students on the 1955 trip.

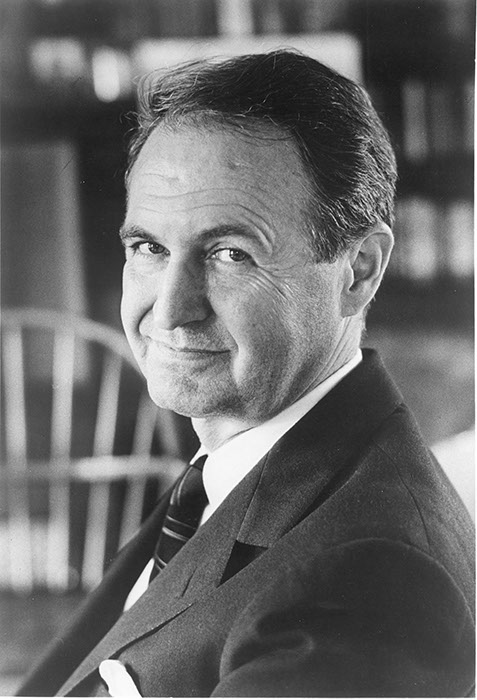

Bert James Loewenberg (1905-1974) — History Faculty, 1942-1971, Director of Center for Continuing Education, 1965-1969

In 1951, Bert Loewenberg jointly taught a course called The Individual and American Institutions with Emma Llewellyn and Edward Solomon. The course “was an experimental course in social science…seek[ing] to combine the materials and the methods of various social sciences – history, economics, sociology, anthropology, philosophy – and to focus these methods and materials on the problems of society and the individual.” These three professors agreed that a trip to the TVA would be extremely worthwhile for students. By the simple fact that Loewenberg would be on the trip as well, many students signed up. Loewenberg was extremely popular with students, especially on these trips. Ellen Cory Epstein ’52 said recently, “Mr. Loewenberg was wonderful and funnier than hell…He tried to slip in some history here and there.” In addition to the 1951 trip, Loewenberg went on the 1954 trip.

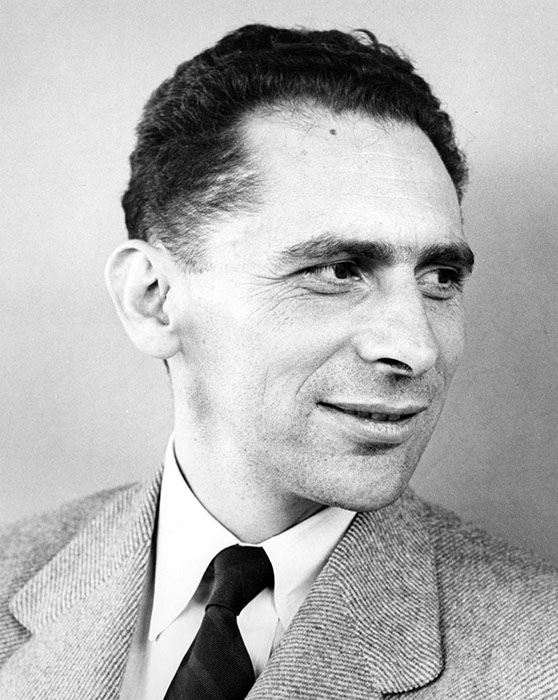

Edward Solomon (1909-1985) — Social Science Faculty/Director of Field Work, 1945-1963

Edward Solomon played a key role in the 1950s trips to the TVA. In fact, he had been pushing for such field trips, as director of field work, for many years and continued to request funds for trips to the TVA after 1955. He traveled with the students on the treacherous extended bus-rides for all three 1950s trips and was responsible for arranging the details of each trip. Esther Raushenbush, in her oral history, referred to Solomon’s “talent for managing field work programs,” which is shown by the success of the TVA trips. In the Herald Tribune article from 1951, Solomon is quoted as saying, “We went for the purpose of studying the South and not for a crusade.” Solomon took this portion of his job very seriously and keenly felt the importance of educating students from the North about the South. In regards to race relations, Solomon was well aware of segregation laws as a Southerner. The Herald Tribune cast Solomon as “a native Southerner with an awareness that ‘we were up against the law, not only a tradition that is fading.