Introduction

Sarah Lawrence College officially became coeducational in 1968 after years of debate and limited admission of men in special circumstances. Like the College’s distinctive pedagogy, the process of coeducation followed a unique path. From the College’s founding as a junior women’s college in 1926 to the admittance of male veterans under the G.I. Bill, to formal coeducation in 1968 and, finally, to the current diverse student population, men have played an important role in the College’s history. Despite the concern of whether or not Sarah Lawrence could maintain its unique pedagogy after admitting men, the College has been officially coeducational for more than half of its history. The change at the College mimics the larger change that took place in higher education nationally.

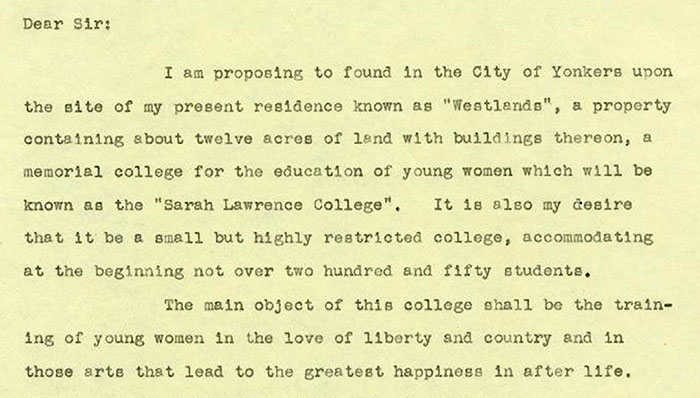

Founding Sarah Lawrence

In 1924, William Van Duzer Lawrence wrote a letter to Chairman of the Board and President of Vassar College, Dr. Henry Noble MacCracken, in which he expressed his wish for the College to be “founded in the belief that there is a woman’s sphere of activities and a man’s sphere of activities in the world, that the border line between these is more or less chaotic...and ought to be more clearly divided...The woman’s sphere...is quite as large as the man’s and we see no just cause for them to leave it and work in the man’s field of action which nature never intended them to do. The Lawrence College proposes to educate its girls to become able and influential leaders in this woman’s world, accomplished in all arts and sciences that tend to elevate and strengthen the race and extend the influence of her sex...”

1930s: Men as Guests

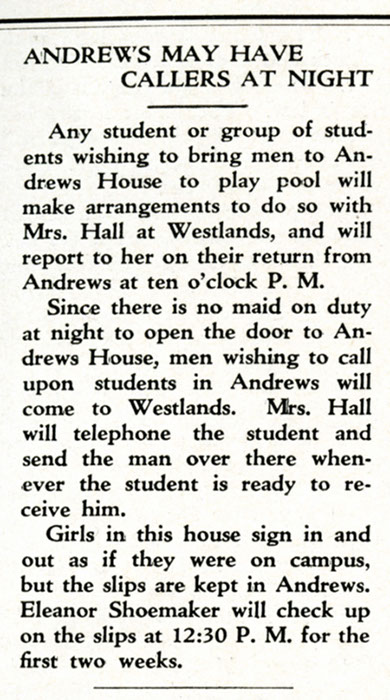

The 1929-1930 College Handbook stated that “men guests may not be entertained in dormitories and may not be taken over campus after dark.” The occasions at which men were allowed on campus, policies for men visiting in dorms, and the behavior of students and their dates upon returning late to campus were common discussions in Student Council and in student newspaper editorials.

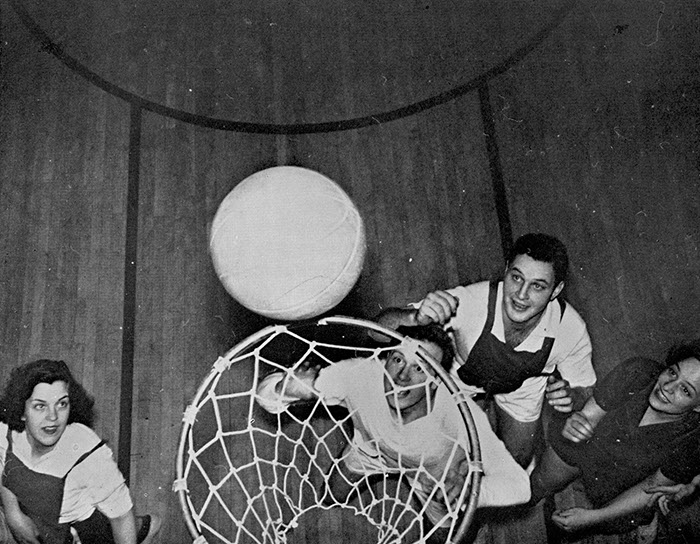

Athletic matches were also an occasion for men to visit. Men’s basketball and baseball teams were hosted on campus for friendly competition with the women’s teams. Sometimes the teams were coeducational.

By the 1932-1933 academic year students were allowed to have male guests in Westlands until 11 p.m. and in the dormitories with special permission. Men were also permitted on campus after dark but only for plays, concerts, and Sunday Vespers.

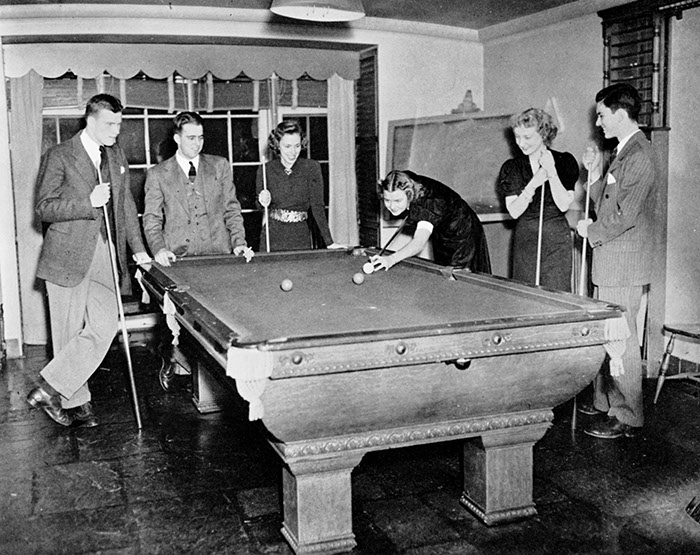

Later in the 1930s students were allowed to entertain men in all dormitory living rooms, on the main floor of Sheffield Studios, the MacCracken basement, and the Andrews Pool Room. And, by 1940, men were allowed to visit students’ rooms during certain hours of prom weekend.

The Impact of World War ll

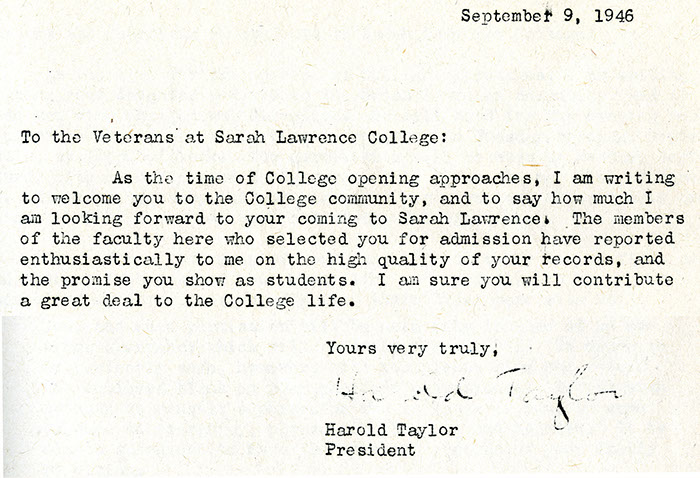

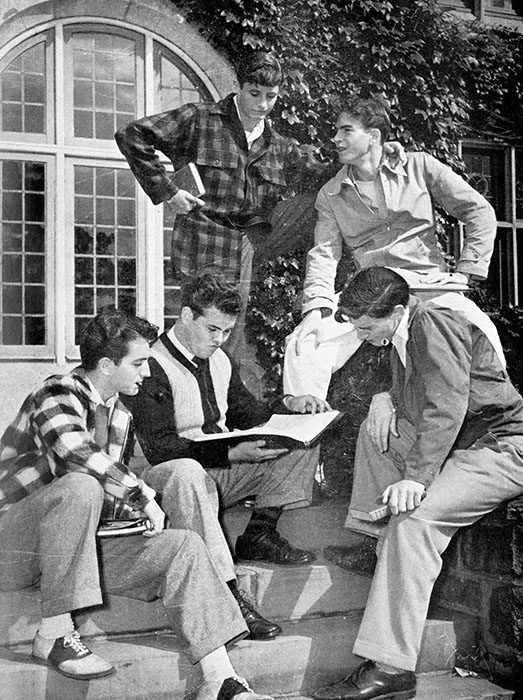

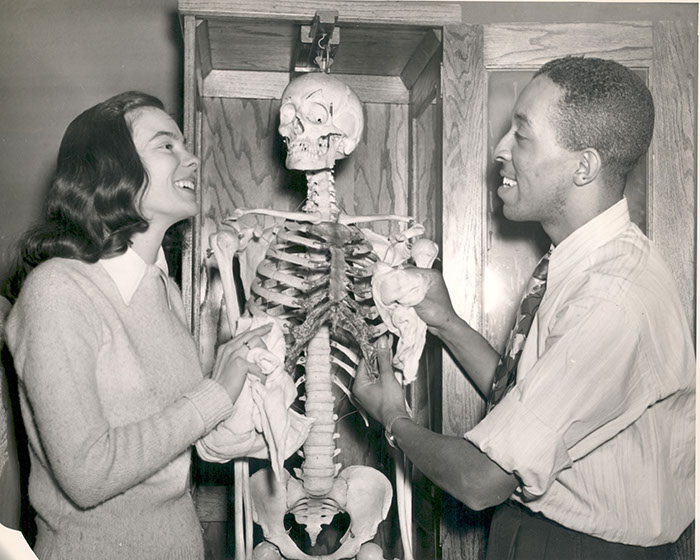

At a March 1946 faculty meeting, the faculty discussed the topic of admitting men to Sarah Lawrence under the context of helping to ease the enrollment burden felt by the state. The following month the faculty passed a motion to accept a limited number of veterans to the College as day students. The first veterans were admitted in the fall of 1946. This group consisted of 36 male veterans, 3 women from the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), and 1 woman from the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES).

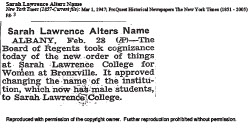

The New York Times reported in March 1947 that the State Board of Regents approved a change in the name of the College from Sarah Lawrence College for Women to Sarah Lawrence College, reflecting a change in the College’s plan to award bachelor’s degrees to men.

“With the arrival of warm weather we tried to take the sight of innumerable bare female legs in our stride. We were obviously excluded from the sun-bathing on the roof of MacCracken. We approached lounge rooms noisily, perhaps jangling keys or coughing...we noticed, though, that at Sarah Lawrence the giggling co-ed was replaced by a culturally jam-packed type of woman, and we strove to maintain our own air of cultural elegance.” - Veteran Joseph Papaleo ‘49, Literature and Writing Faculty Emeritus, 1960-1992.

The last veterans graduated in 1951. In total, 44 veterans were admitted to the College and 32 of these students graduated. The program was viewed, by and large, as a success for the College. In a 1957 report on the veterans, faculty member Irving Goldman wrote that veteran alumni credited “the overall atmosphere of the college, the stimulation of ideas from faculty and students, and the opportunities for doing independent work” as leading factors in their successful careers after Sarah Lawrence. This feedback promoted the idea that a Sarah Lawrence education was as effective and profitable for men as it had proven to be for women.

Graduate Programs Admit Men

Men and the Theatre Program

Beginning in the early 1930s, men participated in Sarah Lawrence theatre productions. As veterans came to campus in the postwar period, many contributed to dramatics activities in their coursework, as actors, or by working on productions. In November of 1952 the Board of Trustees approved the participation of men in the performing arts program, with academic credit to be transferred toward an undergraduate degree at other colleges.

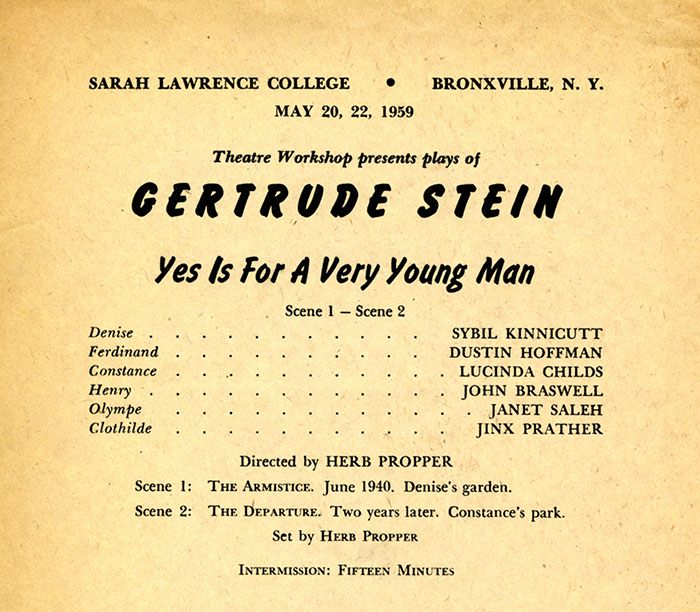

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s many male graduate students were active in theatre as well. Prior to official coeducation, the College also hired actors to fill male roles in campus performances such as the 1959 production of Gertrude Stein’s Yes Is For A Very Young Man featuring Dustin Hoffman.

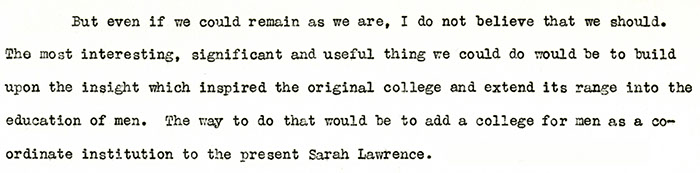

The Coed Discussion

In 1956, ten years after the admittance of the first men to Sarah Lawrence College, President Harold Taylor wrote to the Trustee-Faculty Committee on Planning and Finance that “...the next step for Sarah Lawrence to take is to establish a college for men, co-ordinate with the present institution for women...” This statement was influenced both by the financial situation of the College and acknowledgement that the dynamic educational system had changed with the influx of students, both male and female. President Taylor believed that with the right student body Sarah Lawrence could further its unique pedagogy.

On April 15, 1957 faculty member Irving Goldman presented a “Report on the Sarah Lawrence Veterans.” The report, based on student records and questionnaires, provided a summary of the veteran student experience on campus as well as the impact of a Sarah Lawrence education on their achievements later in life. As part of the questionnaire, respondents were asked how their education helped in their careers, what the most important things they got out of the College were, and what were their criticisms and views on a Sarah Lawrence education for men.

The majority of respondents asserted that the type of education Sarah Lawrence College offers is equally as effective and valuable for men as it is for women. One veteran wrote that, “If Sarah Lawrence’s kind of education had any validity (and I believe it does), that validity starts and ends with each student’s ability to learn and does not stop at the side on which he or she buttons his or her coat.”

Another student responded by saying, “There may be a different outlook men and women who are going into business or profession have from those who are not...but education can’t be ‘good’ for one sex and not for the other.”A few of the alumni criticized the lack of real workforce preparation, a concern that was shared by the Faculty Committee on Planning the Future of the College. As the College continued to face financial hardship, the debate about increasing enrollment through coeducation and the establishment of a coordinate men’s college persisted.

Official Coeducation

During the early and mid-1960s the College continued to look for ways in which it could be more successful in light of the national trends of increasing college enrollments, expansion of large research universities, and a shift in funding from private individuals to state and public resources. Small liberal arts colleges, like Sarah Lawrence, felt these changes acutely. As Dean of the College and then President, Esther Raushenbush oversaw decisions and discussion leading up to the College’s official coeducation in 1968. In 1965, Raushenbush wrote about both size and diversification at Sarah Lawrence. In her “Future of the College” statement she proposed that the faculty consider the possibility of establishing a coordinate men’s college for the benefit of raising enrollment without actually increasing the size of the women’s college.

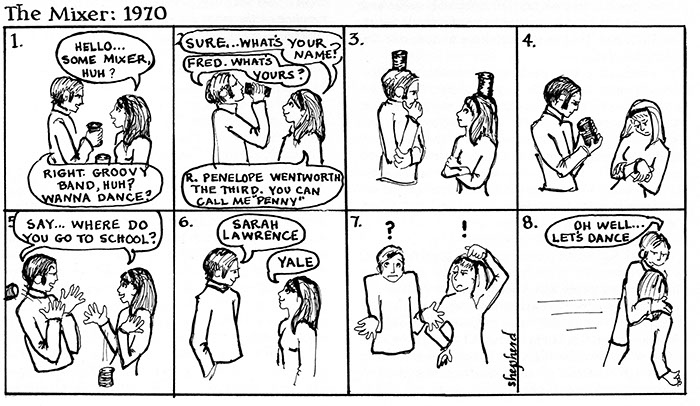

Unlike many other colleges contemplating coeducation, Sarah Lawrence did not choose to undergo a lengthy self-study. In fact the admittance of men in 1968 was an acknowledged trial in coeducation by the College with a report to be completed in the fall of 1972 by President Charles DeCarlo. By 1972, there were 54 male resident students and 14 day students. Discussion about the suitable ratio of male to female students continued through the 1970s and into the 1980s. The College brainstormed ideas for recruitment, such as promotional brochures specifically designed for men and the development of intramural/intercollegiate programs. In addition the College considered curricular expansion in the social sciences, math, and science. Sarah Lawrence students attended “co-ed weeks” hosted by other northeastern colleges and the College held its own Coeducation Week in February of 1969. Men from nearby colleges stayed on campus for one week attending classes, performances, and meeting with the president.

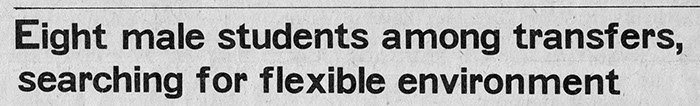

In the spring of 1967, after deciding against a proposed affiliation with Princeton University, the Board of Trustees announced that beginning in the fall of 1967 the administration was authorized to admit a limited number of men as regular undergraduate students, able to study any fields and earn academic credit towards a bachelor’s degree to be granted by the College. The Board also recommended that a long-range study be planned to report on the coeducation decision. By January of 1968, six men had entered the College as transfer students. Five of them lived on campus in Perkins House.

The first official coeducational class at Sarah Lawrence College was initially met with a mixed reception. The concern on the part of some students, faculty and administrators was that the introduction of men into the College would irrevocably alter the nature of the school. They feared that men would cause a distraction, change the curriculum and dilute the quality of the student body. Others argued that a coeducational model was fairer for both sexes, and that a single sex education was not as socially or intellectually healthy. Some faculty members observed that men and women at the College often complimented each other intellectually in and out of the classroom.

“The women seemed surprised that the range of the ability of the men was about the same as the women. It was as if the women’s perceptions of men were demystified.”

Charlotte Doyle, Psychology Faculty, Sarah Lawrence 1966 –

“In spite of all the opposition, as someone who came through a co-ed system, I felt women needed to learn how to function in an environment with men. I was a strong supporter but it was contentious.”

Margery Franklin, Psychology Faculty Emerita, Sarah Lawrence 1965 – 2002

“I was not that happy about coeducation for the simple reason that I felt Sarah Lawrence had a certain identity as a women’s college and it was important in the United States to have a women’s college. I felt that a real distinction we had vanished with that…. On the whole I would say I was not aware that any great change was made other than changing the gender identity of the college.”

Hyman Kleinman, Literature Faculty Emeritus, Sarah Lawrence 1964 – 1984

“SLC was very ambivalent. Unlike Vassar which used affirmative action, we never did that, we were never as gung-ho.”

Fred Smoler ‘75, History Faculty, Sarah Lawrence 1987 –

“Numerous professors and alumnae didn’t want Sarah Lawrence to change. Several feminist students wanted Sarah Lawrence to be a ‘citadel against male aggression’.”

Ilja Wachs, Literature Faculty, Dean of the College, Sarah Lawrence 1965 –

“I suspect the reason we went co-ed was a survival move. We were nearly bankrupt by the late 60s. It was a horrific financial situation at the time. It couldn’t hurt to double the potential pool. More important, why don’t men deserve the best education in America? When I sit with alums, skeptical of integration, this usually quiets them.”

Micheal Rengers ‘78, Vice President of Operations, Sarah Lawrence 1978 – 1981; 1984 – 2010

The Student Body Ratio

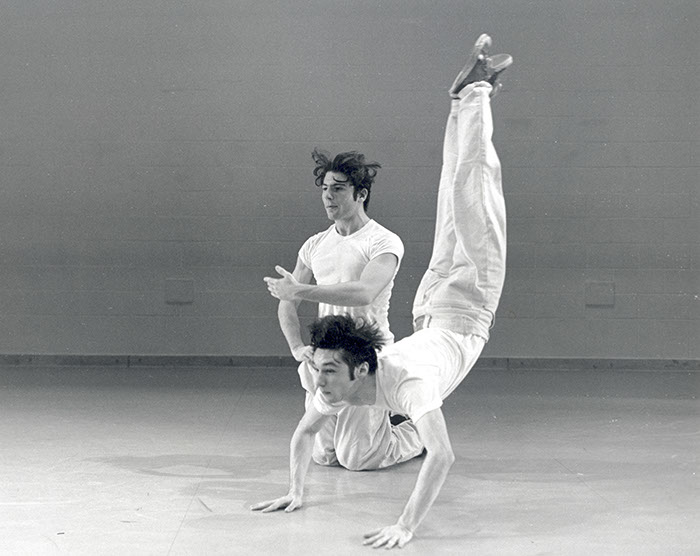

Perpetually shy of the critical mass to reach equilibrium between the sexes, Sarah Lawrence College has always had a roughly 75%-25% split between women and men. Many have argued the school should strive for greater parity. Many have argued equally passionately that the ratio is fine as it is. Despite the controversy and debate over the ratio, many men have been successful in their fields as a result of the Sarah Lawrence pedagogy: Among them are White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel ‘81, film-maker J.J. Abrams ’88, Pulitzer Prize winning playwright David Lindsey Abaire’92, acclaimed dancers John Jasperse ‘85, Rashaun Mitchell ’00, and Christopher Williams ‘98, senior attorney Mark P. Goodman ’83, and ground-breaking neurobiologist W. Ian Lipkin ’74.

“This silly report came out saying that we were a women’s college which admits men and essentially guaranteed coeducation to never fully take root…They’ve made it a healthier, richer and more diverse place…It’s crazy that we can’t get men to come here to enjoy the benefits of this wonderful education. It’s the lack of critical mass that keeps men from coming. Men need the feeling, especially as freshmen of being part of a community.

Ilja Wachs, Literature Faculty, Dean of the College, Sarah Lawrence 1965 –

“We were all surprised by the high quality of the applications. They were really astonishingly good. A lot of them were transfer students, who often had come from places they were very unhappy with. I remember several from Dartmouth and Princeton. These were still very dark, cold traditional places...Certainly some of my best students over the years have been men.”

Danny Kaiser, Literature Faculty, Sarah Lawrence 1964 –

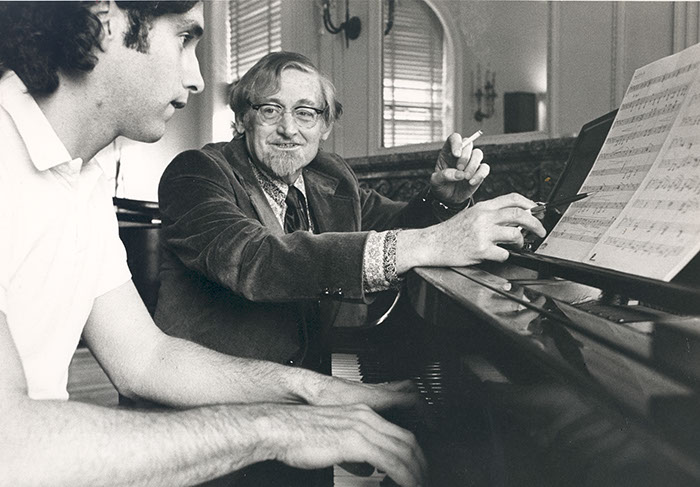

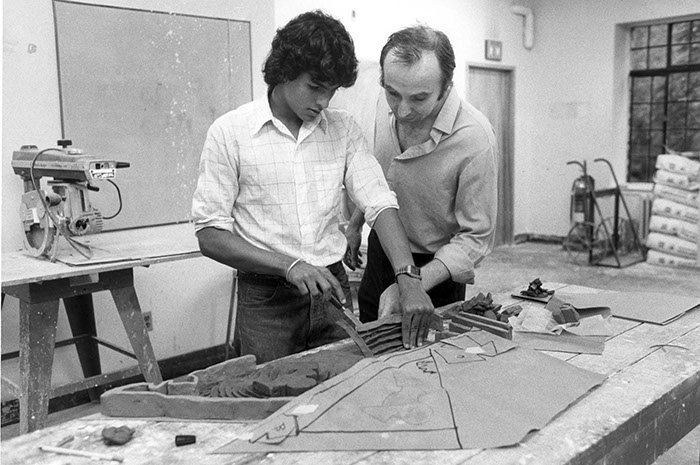

A Distinctive Brand of Coeducation

Esther Raushenbush wrote in her 1968 “State of the College” address that “...if good men students have some good reason to study here, either because of something we offer, or how we teach, or our location, or any combination of these, they should come here to study.”

“Some faculty members were on the fence; they feared they would have to change the curriculum. There were others who were afraid that somehow the culture and intimacy of SLC would be altered. None of this came true.”

Ilja Wachs, Literature Faculty, Dean of the College, Sarah Lawrence 1965–

“It was the first time in my life where I would be turned to in a class and asked, ‘well what do men think about this?"’

Micheal Rengers ‘78, Vice President of Operations, Sarah Lawrence 1978 –1981; 1984 – 2010

“Faculty had reservations that some of the young women had. They were concerned that the women would be awed by the presence of men…the feeling among the faculty was that men would dominate classes and discussions. This wasn’t so.”

Hyman Kleinman, Literature Faculty Emeritus, Sarah Lawrence 1964 – 1984

“I think that having men has been wonderful for the dance department. The curriculum has not changed at all because of them, but it gives choreographers different kinds of choices in making dances.”

Rose Anne Thom, Dance Faculty, Sarah Lawrence 1975–