Read on for announcements, interviews, event recaps, and more from our Writing Institute community.

Three Questions with Instructor Eileen Moskowitz-Palma

December 23, 2025

Eileen Moskowitz-Palma is returning to the Writing Institute as an instructor in 2026 to teach her class Structuring Your Novel. Eileen previously taught fiction for the Writing Institute for seven years, and is back now after a few years off to write and promote her middle grade book series.

Three Questions with New Instructor Brandon Childs

December 14, 2025

Brandon Childs is joining the Writing Institute as an instructor in 2026 and will be teaching Intro to Screenwriting! Brandon is a writer, actor, and director, who has worked on a wide variety of TV projects.

What I Learned at Craft Weekend

October 17, 2025

Our second annual Craft Weekend is in the books! It was such a treat to participate as both an instructor and attendee. As the Graduate Assistant for the Writing Institute, I know how much work and planning went on behind the scenes to pull off the weekend smoothly, so it was extra rewarding to see it all come together.

My Three Favorite Things About Writers Week

September 17, 2025

Since 1999, Writers Week at Sarah Lawrence College has offered creative young people an immersive week-long experience in creative writing and the performance arts, and since 2023, the program has taken up special residence in my life and work!

Three Tips From A Top Literary Agent

February 19, 2025

Last week, we were thrilled to host literary agent Jamie Carr of The Book Group for a conversation with Assistant Director and debut novelist Ava Robinson. When Ava got off the phone with Jamie after their first meeting, she knew she’d found her match.

2024 Writing Institute Year in Review

January 7, 2025

I am filled with gratitude when I think about each of the writers who showed up with our community in 2024. Whether your intention for the new year is to write a single page or finish a full manuscript, to read more poetry or try a new genre, we look forward to being part of your writing journey once more.

Celebrating Twenty Five Years of Writers Week

October 4, 2024

This past summer we celebrated our 25th season of Writers Week. In collaboration with the Sarah Lawrence College Theatre Program, Writers Week is our largest program at the Writing Institute. The program offers a week-long immersive experience in creative writing and performance art to young writers 14 to 18 from across the country and (with our virtual week) around the world.

Finding Inspiration as a Disabled Writer at The Writing Institute at Sarah Lawrence College

June 18, 2024

I wrote my memoir alone for seven years. I wrote at my desk. I wrote at the kitchen table. I wrote in bed. After my son Noah was born, I then began writing in between naps. However, I never wrote personal stories in a group setting before Kathy Curto’s Memoir Intensive class through the Writing Institute at Sarah Lawrence College.

Express Yourself. How the Writing Institute Supports MFA Students and Yonkers Teens

May 23, 2024

When a spring storm shook 45 Wrexham’s windows, Master of Fine Arts in Writing candidates and Yonkers middle school students did what many do during inhospitable weather: they swapped stories.

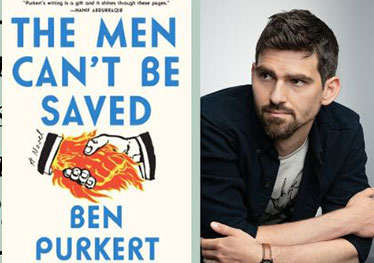

Meet New Writing Institute Instructor Ben Purkert

May 15, 2024

We’re so excited to welcome Ben Purkert as a Writing Institute instructor this summer! He’ll be teaching a one day course, Winning at the Finish Line.

Event Recap: Writers and Cats at AWP 2024

February 10, 2024

If there's one thing we know about writers, it's that they love cats! Or at least we had a pretty good hunch when we decided to host “Writers on Cats: an AWP Offsite Reading” earlier this month at the 2024 Association of Writers and Writing Programs Conference, held in Kansas City, Missouri.

2023 Year in Review

December 31, 2023

As we close out the year, we wanted to celebrate all of our accomplishments in 2023, our 40th anniversary year. Read on for our year in review, and we hope you'll take a moment to recognize your own writing milestones this year.

Angie Hunt Interview

November 15, 2023

Angie Hunt, a Writing Institute student, sat down for a conversation with classmate Lucia Greenhouse, author of the recently published fathermothergod: My Journey Out of Christian Science.

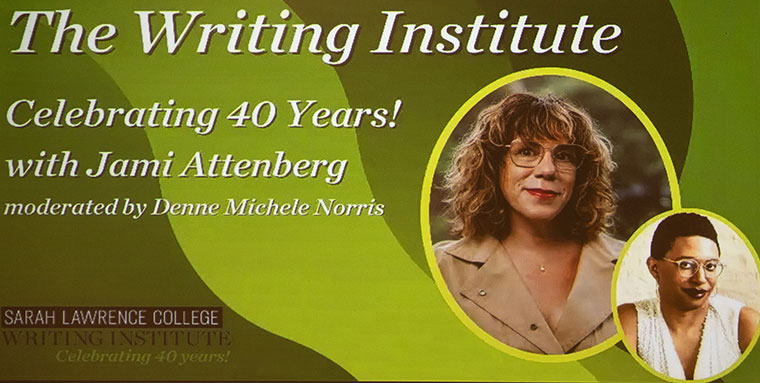

Event Recap: 40th Anniversary Event with Jami Attenberg

October 15, 2023

When it came time to plan our 40th anniversary celebration we could think of no better writer to embody the tenacity and altruism of our community than Jami Attenberg. The author of more than ten books and creator of the grassroots #1000WordsofSummer writing accountability group, Jami knows the value of writing together.

Trina Traster in Conversation with Carolyn O'Laughlin on Her Memoir

September 15, 2023

"It was an intense privilege," says Tina Traster, "to be able to sit and think and write about the most important thing." The writer says it was during the week she spent at the 2009 Summer Seminar for Writers that seeds were planted for her memoir about her family's story of adopting a Russian child.

Stephanie Cooper and Howard Weinberg Interview

August 15, 2023

Stephanie Cooper and Howard Weinberg talk about their experiences at The Writing Institute and discuss what it's like taking a class with their significant other.

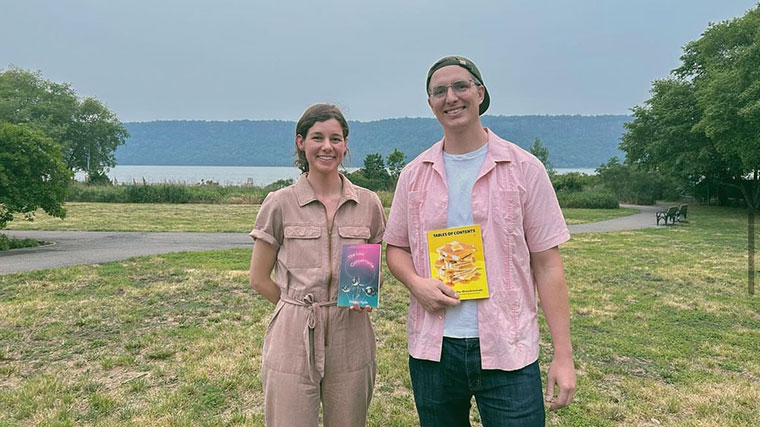

Books on the Barge

July 1, 2023

On June 17, 2023, the Writing Institute co-hosted the first Books on the Barge event with Groundwork Hudson Valley and Tables of Contents. This unique literary event focused on climate fiction, with small bites inspired by Allegra Hyde’s short story collection The Last Catastrophe.